In the 21st century, organizations are going to need to become more decentralized and interconnected if they want to adapt to our new fast-paced world. Here’s how a “team of teams” mindset helps accomplish that.

Today’s world is filled with more information than ever before and it’s becoming increasingly more complex.

One might think in our current technological age – and with the growing amount of “big data” – that it might become easier for bosses, politicians, and leaders to predict the behavior of large groups of people.

The logic is that the more data we can collect from people (including even their Twitter feeds, Facebook likes, and Amazon purchases), then the easier it is to understand human behavior and manage it.

However, this is based on a faulty understanding of human behavior. We tend to think that humans are like a machine with “inputs” and “outputs,” so as long as we know the right “inputs” then we can change behavior how we want to.

But the truth is that these “inputs” and “outputs” are more like a series of interconnected feedback loops. Human organization isn’t like a “machine,” it’s like a “living organism” that continuously evolves and feeds off of itself in unpredictable ways.

Therefore, building a successful organization (whether a business, a government, a nonprofit, or even a sports team) isn’t about creating the “right machine,” but creating a “living organism” where all the parts work together organically.

This is one of the major themes in Stanley McChrystal’s new book Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World.

As a general in the U.S. military, McChrystal traditionally viewed human organization as a top-down, “command and control” hierarchy. Leaders gave orders down to their subordinates, and if you send the right orders down the chain-of-command (if you have the “right inputs” going into the “right machine”), then you’ll be successful.

For centuries, this model of human organization had been very effective and common among governments, businesses, and armies. But McChrystal was beginning to find it no longer worked in our current environment.

General McChrystal was involved in the war in Iraq in the 2000s. He knew that when it came to technology, training, intelligence, and manpower, the U.S. was an easy win against Al Qaeda on paper. Yet they weren’t winning at all.

After years of frustration, failure, and confusion, McChrystal was slowly discovering that the key difference between the U.S. Army and Al Qaeda was in their “organizational structure.”

Al Qaeda was a very decentralized and fluid entity. You could discover secret information about them, or take out some of their key leaders, but the group always seemed to be able to adapt quickly and regroup itself. There wasn’t a strict hierarchy, or a long chain-of-command to make decisions, so Al Qaeda was always one step ahead of the U.S.

On the other hand, the U.S. military was a very hierarchical and specialized entity. They were much more rigid in their organizational structure than Al Qaeda. And while this increased their efficiency and power, it ultimately decreased the “adaptability” they needed to make progress.

The U.S. military was a “super machine,” but Al Qaeda was a “living organism.” That was the key difference in their organizational structure. That’s what made them more adaptable and resilient.

In traditional terms, the U.S. military had an “MECE”-like management structure, which stands for “Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive.” MECE is a tidy and effective way to breakdown an organization into separate categories, but this model is becoming increasingly more irrelevant.

The basic idea behind MECE is that if every individual department does their job, then the organization will run efficiently, even if no single department has an understanding of the “whole.”

For example, every individual branch of the military was highly specialized (whether it be the U.S. Army, Navy Seals, Special Forces, Marines, CIA, etc.), but there weren’t many connections between branches, and that stifled the organizations ability to adapt, evolve, and work as a coherent entity.

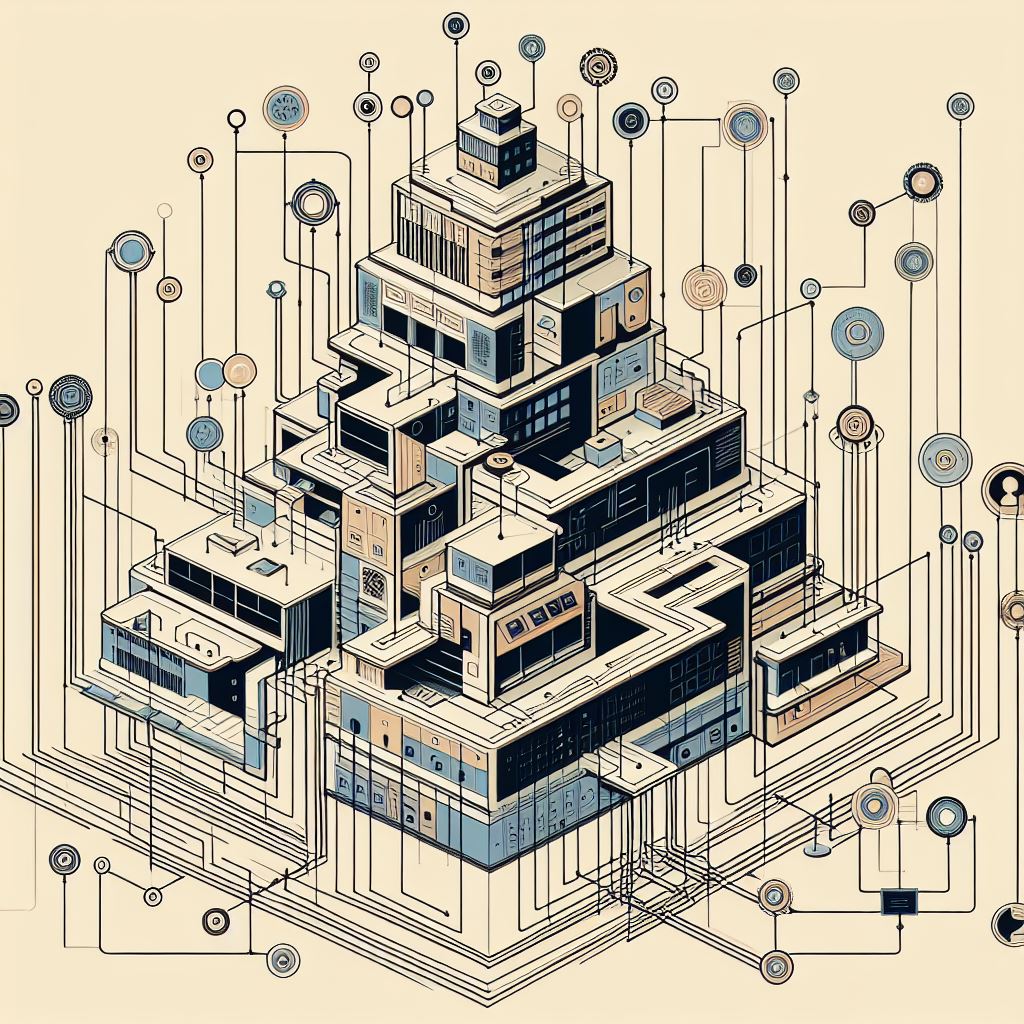

Here is a visual representation of the “MECE” structure compared to a “non-MECE” structure (where different departments overlap and feed into one another):

A “team of teams” mindset requires different departments within an organization to become more overlapping and interconnected.

General Stanley McChrystal knew that he needed to help transform the U.S. military from an MECE structure to a non-MECE structure if they were going to evolve into the 21st century.

Here are the key principles he discovered behind creating a more complex, bottom-up organization.

Shared Consciousness

One important factor in creating an effective organization is to foster “shared consciousness.”

In the past, many organizations tended to operate on a “need to know” basis. It wasn’t important if you understood the main purpose behind an organization (or how other departments operated), as long as you got your particular job done.

This goes back to the old idea that workers are merely “cogs in a wheel.” They don’t need to understand the full system to be effective workers, they just need to focus on their individual area.

In the early 1960s, NASA was losing the “Space Race” to the Soviet Union, who had already produced the first Earth orbiter, the first animal in orbit, the first lunar flyby, and the first lunar impact. When president John F. Kennedy made his famous speech declaring that by the end of the decade the U.S. will have put the first man on the moon, most members of NASA laughed it off and thought Kennedy was daft.

If NASA was going to be the first to put a man on the moon, they knew they had to make some big organizational changes if they were going to succeed. They certainly couldn’t keep things the same.

NASA originally started off as a research project with many different teams working on their own independent projects. Besides monthly meetings between a handful of managers, the teams were largely confined to their own silos without much cross-communication.

Administrator George Mueller was brought in by NASA to shake things up. He insisted on daily communication between teams, so he had NASA build a “teleservices network” that would connect all the project rooms with hard copy, computer data, and an ability to hold teleconferences between different laboratories, manufacturers, and test sites.

This interconnected network at NASA created a sense of “shared consciousness” among the different teams. It transformed a once rigid “MECE” organizational structure to a now overlapping “non-MECE” structure.

If the guys working on the engine were trying to solve a problem, other teams could listen in and potentially offer advice that the engine team may not have been able to think of. This communicative network allowed a more multidisciplinary approach to creative thinking and problem solving.

What Mueller instituted at NASA would later be known as “systems thinking.” This approach is different from the “cog in a wheel” reductionist approach because it believes that “one cannot understand a part of a system without having at least a rudimentary understanding of the whole.”

For example, a doctor can’t fully understand a “hand” by just studying it independently of the rest of the body (like knowing how diabetes can cause the death of tissue in fingers, or that repeated pressure on the median nerve can lead to carpal tunnel syndrome).

Cultivating “shared consciousness” in a business or organization is important because it allows everyone to better understand their part in relation to the whole. It’s not just about your particular department or “team” – you need to think of yourselves as a “team of teams” working together.

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World is an incisive look into how organizations and businesses need to grow and adapt into the 21st century. General McChrystal draws on research from organizational psychology and combines it with his own experiences working in the U.S. military.

Individual Empowerment

Since our world is becoming increasingly more complex and fast-paced, it’s becoming more difficult for leaders and bosses to give orders in a “top down” fashion.

If every decision needs to get approved by someone higher up, that can often stall an organization from being able to adapt to new situations quickly and effectively. To be able to adapt, organizations need to practice a type of “individual empowerment.”

In the year 1805, British admiral Horatio Nelson was preparing for a battle against Napoleon’s Franco-Spanish fleet. His navy was outnumbered and by all accounts it looked as though he would lose the battle. Fortunately, he had a trick up his sleeves.

Traditionally, naval battles were fought with ships lined up in a straight line parallel to their enemy. This maximized the use of canon array – but it also gave commanders a way to give “top down” commands by placing themselves in the center of the fleet and issuing orders through flag signaling.

Nelson’s plan was to instead line up all his ships perpendicular to the center of Napoleon’s fleet, thereby breaking up the center, and cutting off Napoleon’s ability to send orders to the other ships.

Once piercing the center, chaos was created among Napoleon’s fleet because their centralized authority had been taken down, and they could no longer take orders or operate effectively without it. Meanwhile, every ship in Nelson’s fleet was given permission prior to battle to make its own decisions independent of a centralized authority.

That day Nelson defeated Napoleon’s fleet without losing a single vessel, proving the superior strategy of the British Royal Navy. This later came to be known as the “Nelson Touch” – which is the idea that individual commanders should act on their own initiative after the melee has begun.

This is just one illustration of the superiority of “decentralized” authority vs. “centralized” authority. Decentralization allows you to better adapt to chaos and unexpected circumstances.

While leaders may be tempted to micromanage every decision that happens in their organization, this can often backfire tremendously. Not only is it stressful and time-consuming for everyone, but it also limits an organization’s ability to maximize group intelligence and problem-solving on the fly.

The social scientist Friedrich von Hayek wrote a famous essay called, “The Use of Knowledge in Society” which emphasizes how each individual only knows a small fraction of what is known collectively – and as a result, decisions are best made by those with local knowledge rather than by a central authority.

Even the smartest of leaders can only know a small fraction of everything that makes their organization work, so it’s important for them to sometimes take a “hands off” approach and let individuals and teams who are closest to the problem handle it themselves (because many times they are better equipped to handle it).

Individual empowerment within organizations is not only more productive, it can also give individuals a stronger feeling of commitment to their organization. By giving individuals freedom to make their own decisions, they take greater care and pride in their work and don’t feel like meaningless “cogs in a wheel.”

Creating an effective “team of teams” means allowing every individual to be their own “leader” depending on the circumstances and situation.

Leading Like a Gardener

Although Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World has a lot about team-building and making organizations less rigid and hierarchical, the book also realizes that leaders still play an important rule in the future of organizations.

However, the role of the 21st century “leader” has changed.

We used to think of “leaders” as a type of chess master who has complete control over all of the parts and carefully plans their every move, but today’s “leaders” are more like a gardener than a chess master.

The goal of the gardener is to create and maintain the right environment for the plants to flourish. While gardeners aren’t responsible for the growth of every individual plant, they are responsible for daily watering, weeding, and protecting plants from rabbits and disease.

In the same way, today’s leaders have to move away from micromanaging and instead focus on creating the right environment for individuals to work together, build teams, and adapt in real-time.

Instead of seeing an organization as a “machine” where you only need a leader to plug in the right inputs, organizations need to be seen as a “living organism” that needs a certain type of environment to grow and evolve.

The role of today’s leaders is to foster that environment – which ultimately requires an interconnected “team of teams” mindset.

Enter your email to stay updated on new articles in self improvement: