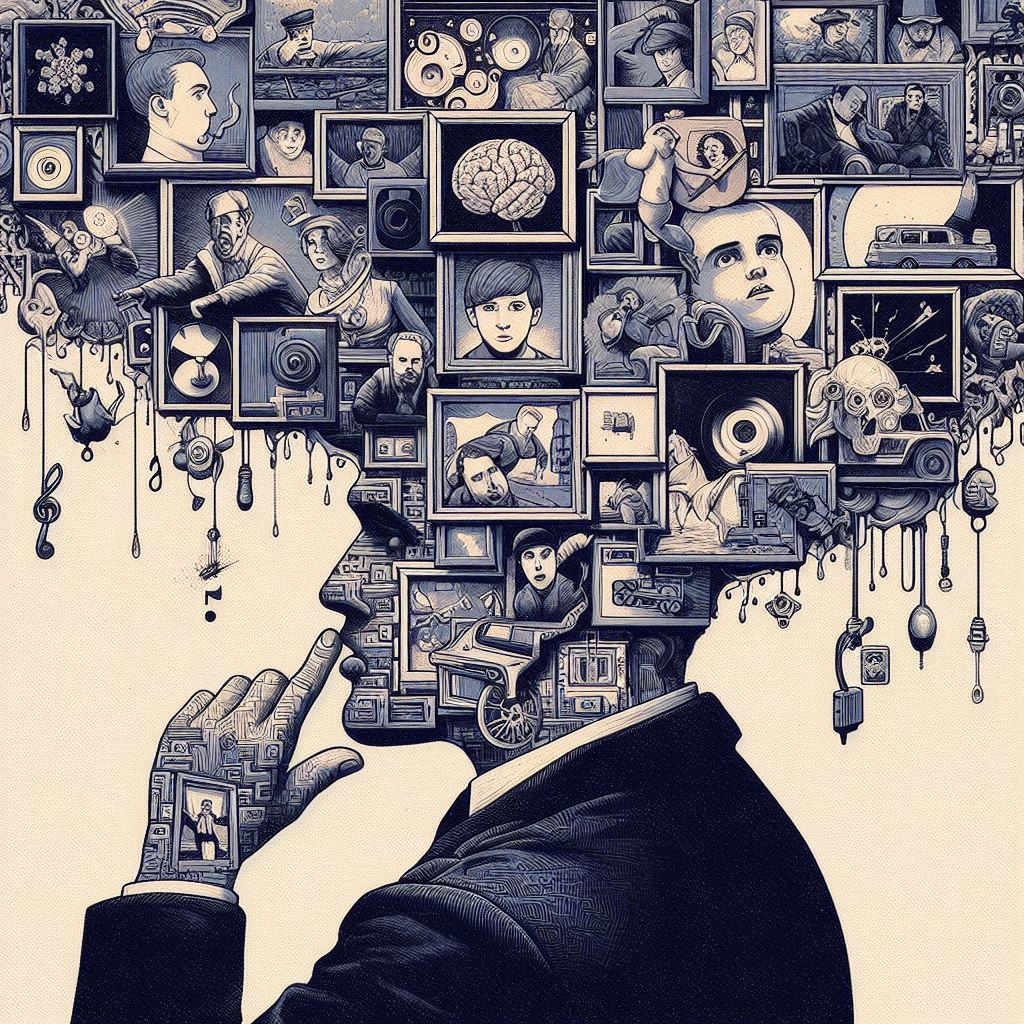

Mnemonics are a forgotten art of memory that today is only practiced among a small group of mental athletes and memory experts. Here’s a great introduction to the techniques they use to master their minds.

There once was a time when memory was the foundation of an intelligent person. Before books, cellphones, and computers, everything a person learned had to be stored inside their mind.

In Ancient Greece, scholars would use elaborate memory techniques to remember full speeches, poems, stories, and historical facts.

Today we don’t have as much of a need to learn these memory techniques (often referred to as “mnemonics”). We don’t need to “internalize” memories, because we can just “externalize” our memories in whatever device we are closest to.

For example, how often do you really remember someone’s phone number? You probably just enter it into your phone right away as someone tells you it. Or at worse you write it down on a piece of paper.

One interesting study published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior demonstrated how our reliance on smart phones leads to more “lazy thinking.” In many ways, technology teaches us that we don’t have to use our brains anymore – we can rely on external devices to do all the “thinking” and “memorizing” for us.

Of course technology has been a huge benefit to society, but in what ways might it be hurting our ability to think sharper and be more cognitively fit?

Can learning mnemonics and the “art of memory” still benefit us today?

Mnemonics: The Forgotten Art of Memory

Mnemonics was a once common art of using particular techniques to improve the strength of you memories. These techniques were popular back when people really needed to rely on their mind’s ability to keep track of information.

In Joshua Foer’s fascinating book Moonwalking With Einstein, Foer goes on a year long journey learning these different techniques from the greatest memory experts in the world, and eventually competes in the U.S. Memory Championship and World Memory Championship.

Those who compete in these memory championships call themselves mental athletes – they work to achieve cognitive abilities that most people would consider a type of superpower.

They spend many hours deliberately practicing these techniques to the point of perfection, all in the name of remembering decks of cards, long strings of numbers, lists of names and faces, and other seemingly trivial facts.

Many of these mental athletes are the last bastion of people still seriously practicing mnemonics and the “art of memory.”

“Moonwalking With Einstein” is a fantastic introduction to this particular world, but I’ll try my best to introduce some of the ideas here. First we need to know more about how memory works.

How Memory Works

Memory is our brain’s ability to encode, store, and retrieve information. Psychologists often separate memory into 2 main categories: Short-term memory and Long-term memory.

Short-term memory (or “working memory”) is our ability to retain information for short periods of time, usually between a few seconds to a minute.

In George Miller’s famous paper, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” it was discovered that the average person’s short-term memory is about 7 bits of information at a time (or plus or minus two, so between 5-9 bits of information).

One ability to improve short-term memory is a process known as chunking, where several bits of information get processed as one. This technique is common in phone numbers. For example, the number “132-546-7891” is 10 bits of information chunked into 3 bits, making it easier to remember.

Long-term memory is our ability to retain information for much longer periods of time (hours, days, months, years). Often how an experience is processed and encoded when in our “short-term memory” is going to influence how well it sticks in our “long-term memory.”

Most of what we process on a daily basis gets easily forgotten. Our brain is constantly sifting through our experiences, deciding what information is worth keeping and what information to get rid of.

A very limited amount of what we experience is actually remembered, some research suggests we only retain about 10% from any given lecture or presentation. That’s why it’s so important to learn how to get ideas to stick both for yourself and when communicating to others.

To put it simply, it takes too many mental resources to remember every single detail of our day, so our brain filters through information and decides what is meaningful and significant. This is usually what gets stored in our long-term memory.

What Makes a Memory Stick?

The art of memory is the art of building rich associations.

The more associations that are built with a certain memory, the more that memory is going to stick in your brain. It’s difficult to remember an isolated fact, but it’s much easier to remember a fact that is embedded in a rich context.

One of the pearls of wisdom Joshua Foer receives in Moonwalking With Einstein is that, “it takes knowledge to build knowledge.”

A dedicated baseball fan is more likely to remember the details of an inning than someone who has never watched baseball before. Our memories of events depend on how well we can put them into context.

When Foer went sight-seeing in China, he was mesmerized, but he couldn’t really remember much of the details of the event because he had no prior knowledge of Chinese history to relate it to. He had no context to fill the details in. At best, he could only remember some basic facts.

Mnemonics depends on our ability to build richer associations with whatever it is we are trying to remember.

You may remember some mnemonics used in school, such as singing your ABC’s to remember the alphabet, or using a picture to help remember words, or a simple phrase like “Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally” as a way to remember mathematical operations.

(Parenthesis, Exponents, Multiplication, Division, Addition, Subtraction – you see, I still remember!)

All of these mnemonic devices are ways to build more memorable associations with what we want to learn. These mnemonic techniques often make it easier to remember something rather than through simple repetition or rote learning.

Memory Palace: Use Imagination to Build Stronger Associations

Mnemonics is ultimately an exercise in using your imagination.

When mental athletes try to remember a list of objects, they often visualize each object in their mind’s eye in a vivid and unique way that’s hard to forget even if they wanted to.

Mnemonics as practiced by mental athletes can be broken down into 2 main abilities:

- Visualization – This is the ability to create a visual representation of what you want to remember and see it clearly in your minds eye.

- Spatial Awareness – This is the ability to store each visualization in an orderly mental space.

Many who practice mnemonics create what is known as a “memory palace.”

A “memory palace” is a detailed memory of an old place that you are super familiar with – you can then use this visual/spatial memory to store new information in an orderly way.

For example, a common “memory palace” for people to use when first starting mnemonics is their childhood home.

Take a moment to think of your own childhood home for a second. You probably still remember where all the rooms are located, and even many particular details about each room (where the TV used to be, where the fridge used to be, etc.)

Now, you can use this memory of your childhood home to remember any list of facts, such as a string of numbers, a deck of cards, or something more practical like your grocery list.

If you were to use this memory palace as a grocery list, you could visualize every item and then store each item throughout your childhood home.

For example, when you first walk in the front door there can be an “Apple” on the welcome mat, and a “Banana” on the kitchen counter, and an “Orange” by the fridge, etc – reminding you that you need to pick up apples, bananas, and oranges at the grocery store.

This is known as the “method of loci” among mental athletes. Interesting new research published in Scientific Advances has shown that this mnemonic technique can improve both short-term memory and long-term memory.

This makes sense. If you’ve ever created a memory palace – and you haven’t used it since then – you can often go back to it and remember a surprising amount of the original information you first stored there, especially if you encoded it properly when first building it.

Mental athletes take their “memory palaces” very seriously. Often they actively visit new places to create new memory palaces, or even look through pictures of mansions in real estate magazines to create bigger memory palaces with more places to store information.

Here’s a simple exercise to practice mnemonics for yourself.

Mnemonics Exercise – “Grocery List”

Now let’s try using mnemonics to remember a grocery list of 20 items.

As an example, let’s start with:

- Apples

- Bread

- Eggs

- Milk

- Turkey

First visualize your childhood home (or your current home) – this will be your “Memory Palace” where you will store your new memories.

Now start outside in front of your home and try to visualize each object in an interesting way:

- Since the first item you have to remember is “Apples,” you could visualize 3 giant Apples outside. Make them smiling, dancing, singing, and having a good time at their Apple party.

- The next item is “Bread,” so you could visualize your mailbox filled with Bread, so much so that it continues overflowing, like a never-ending waterfall of Bread coming out of your mailbox.

- Now we have to remember “Eggs,” so you could visualize yourself opening your front door and the first thing you see in front of you is a complex pyramid of giant Eggs right as you walk in. An Egg pyramid, built by pharaoh Chickens, all the way to the ceiling.

- And the next item is “Milk,” so you could visualize whatever room is to your left being filled up with Milk. Picture a Milk swimming pool just sitting there in the middle of the room, with someone swimming in it.

- The final item is “Turkey,” so you could visualize whatever room is to your right as a Turkey petting zoo, with a bunch of children yelling and screaming as they run around the Turkeys.

This is just an example, but you get the idea. Yours will likely be different depending on your individual “memory palace” as well as your own sense of imagination.

Make a list of 20 objects and try it out for yourself. Give yourself however much time is necessary to go through each item, create a unique visualization, and then store it in your “memory palace.”

Once you feel you’ve built a strong enough memory, hide the list and test yourself to see how many you can remember all on your own.

Try not to be too hard on yourself – learning mnemonics takes deliberate practice and this is only your first attempt! As a beginner, it will take a lot of effort and concentration to build your first memory palace and use it to remember correctly.

You may end up thinking, “This is stupid – I’m just going to write a list with paper and pen the old-fashioned way!” And sure, that’s probably the most practical option if you simply want to go grocery shopping.

But if you want to improve your memory, you’re going to have to put in the work to learn how to use it, even if at first these exercises seem slow or inconvenient.

Once you practice enough, try challenging your friends or family to a memory competition. Make a new list of 20 items, give yourselves 5 minutes to remember as much as possible, then see who can remember the most.

At the very least, it can be a neat little party trick! People will be surprised you can remember the entire list (in order, no less!)

One interesting thing you’ll find is that these memories will last much longer than expected. If you do this exercise effectively once, you’ll still be able to recall the same associations days, weeks, and even months later.

Exaggerate, Exaggerate, Exaggerate!

One general rule of thumb when using mnemonics is that the more exaggerated and bizarre the visualization, the more likely it will stick with you.

This is why it helps to make things really large, or add faces to inanimate objects, or have your images doing really silly things, or make your images defy the laws of physics.

Anything that would make a lasting impression on your mind if you saw it in the real world is likely a good candidate for imprinting a visualization in your memory.

Finding ways to exaggerate and have fun is the key to building effective mental notes. I keep these principles in mind whenever I’m making a quick mental reminder to myself (even if it’s something small like “put out the garbage” or “clean the bathroom”).

In Moonwalking With Einstein, one of Joshua Foer’s teachers tells him to fill his memory palaces with hot women to make them more memorable. And some of the Ancient Greeks were known to make their visualizations disgusting and repulsive to make them stick better.

Of course using your imagination takes practice. You may have a hard time at first thinking of weird and memorable scenarios, but with time and patience they will come to you much easier.

And if you really don’t trust your memory, don’t forget the power of a daily checklist. Mnemonics can be powerful, but you probably shouldn’t completely rely on them to remember things.

Enter your email to stay updated on new articles in self improvement: